Table of Contents

- Concept

- Four different races of being

- Bergdama (Damara)

- Believe of the Damaran

- Bushmen (San People)

- Believes of the San people

- Creation Myth of the San people

- A race of Jinn before the creation of Adam

- Names of little people in myth stories

- Little people in the Middle East

- Subterranean Dwarfs (Iranian Folklore)

- Djinn/Jinn (Widespread in Islamic Mythology)

- Bhoots or Jinn (Afghanistan Folklore)

- Talu (Mesopotamian Mythology)

- Arzshenk (Armenian Mythology)

- Gnomes (Middle Eastern and European Influence)

- Daeva (Zoroastrianism, Ancient Persia)

- Divs (Persian and Zoroastrian Mythology, Iran)

- Chaldean Mythical Beings (Ancient Mesopotamia)

- Peris (Persian Mythology, Iran)

- Pazuzu (Mesopotamian Mythology, Iraq)

- The Armen (Armenian Mythology)

- Shedim (Jewish Mythology)

- Gul (Turkic and Persian Mythology)

- Little people in Africa

- Abatwa (Zulu and Xhosa Mythology)

- Maabara (Sukuma Mythology)

- The Tikoloshe (Zulu Mythology)

- Mmoatia (Ashanti Mythology, Ghana)

- Agogwe (East African Folklore)

- Aziza (Fon and Yoruba Mythology, West Africa)

- Biloko (Central African Folklore)

- Hawane (Swazi Mythology)

- Kaukus (Berber Mythology, North Africa)

- Adze (Ewe Mythology, Ghana and Togo)

- Djinn or Jinn (North African and Swahili Coast)

- Duendes (Cape Verdean Creole Folklore)

- Sasabonsam and Asanbosam (Akan Mythology, Ghana)

- Ninki Nanka (West African Folklore)

- Tokoloshe (Southern African Folklore)

- Hili (Swahili Folklore)

- Americas

- Jogah

- The Gahongas

- The Gandayah

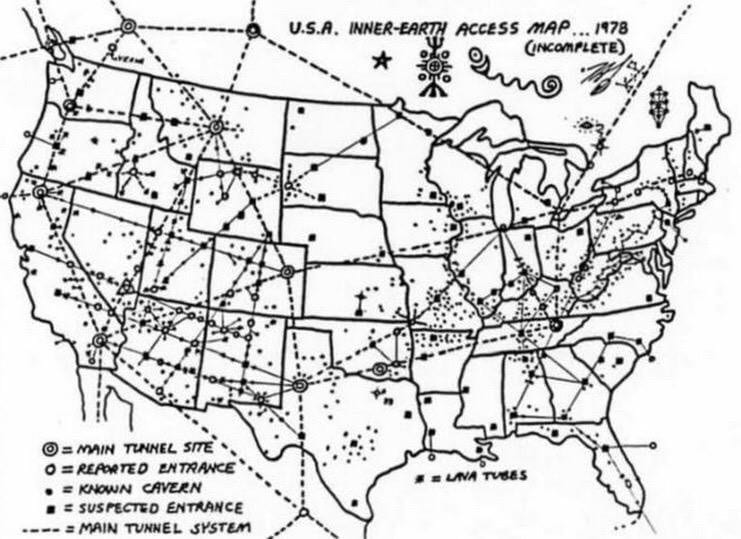

- Mines & Tunnels

Concept

- Third race are little people worked in the mines

- Probably connected to the Jinn

Four different races of being

When the Anunnaki eventually departed the mining fields of Ancient Afrika they left behind four different Races of Beings.

- The first was the Reptilian Race who were the ‘Slave Masters’ of the thousands of Hybrid Humans created to work the multitude of mines.

- The second were the Afro-Atlanteans who were the original inhabitants of the land.

- The third Race was the “Little People” who were created to work the mines and now had no ‘Master’. They would eventually integrate into other African races such as the Bergdama and the Bushman.

- The Fourth Race was the Nephilim — a Being of Giant stature and hated by all. The Nephilim Giants were then systematically wiped out.

“The little people would eventually integrate into other African races such as the Bergdama and the Bushman”

Bergdama (Damara)

- Location: Primarily found in Namibia, the Damara people have been resident in the region for thousands of years.

- Language: They speak the Damara/Nama language, which is notable for its use of click consonants, a feature shared with some other languages in Southern Africa.

- Culture and Livelihood: Traditionally, the Damara were semi-nomadic, engaged in pastoralism and small-scale agriculture. They are known for their skills in working with livestock, particularly goats and sheep.

- History: The history of the Damara people is complex, involving interactions with other ethnic groups in the region, such as the Nama and Herero. During colonial times, they faced significant challenges and disruptions.

- Modern Context: Today, the Damara people are integrated into modern Namibian society but continue to maintain their distinct cultural identity and traditions.

Genetic studies have found that Damara are closely related to neighbouring Himba and Herero people, consistent with an origin from Bantu speakers who shifted to a different language and culture.

The Damaran were also copper-smiths known for their ability to melt copper and used to make ornaments, jewellery, knives and spear heads out of iron.

The Damaran initially settled between Huriǂnaub (Kunene River) and ǃGûǁōb (Kavango River), before entering what later-on centuries long after became known as ǀNaweǃhūb (Ovamboland).

Believe of the Damaran

The primary god revered by the Damaran (ǂNūkhoen) people is ǁGamab, also known by various names such as ǁGammāb (the water provider), ǁGauna (in Sān), ǁGaunab (in Khoekhoe), and Haukhoin (meaning ‘foreigners‘ in Khoekhoe), among the Khoekhoe community.

Residing in a celestial realm higher than the starry sky, ǁGamab, whose name combines the Khoekhoe words for water (ǁGam) and to give (mā), is revered as the giver of water. This deity is associated with the emergence of clouds, along with phenomena such as thunder, lightning, and rainfall. He plays a pivotal role in the natural world, ensuring the seasonal cycle’s continuity and providing wild game to the ǃgarob (Khoekhoe for ‘wilderness’) and the Damaran people. One of his key duties includes fostering crop growth.

Additionally, ǁGamab is acknowledged as the God of Death, controlling human destiny. From his heavenly abode, he is believed to shoot arrows at people, with those struck becoming ill and eventually dying. Upon death, souls are said to journey to ǁGamab’s celestial village located above the stars, where they join him around a sacred fire. Here, they are offered a drink from a bowl of liquid fat as a reward.

In contrast, ǁGamab’s nemesis is the malevolent deity ǁGaunab.

Enlil, Enki, Ea and Adad

In the pantheon of the ancient Mesopotamian religion, including the Anunnaki deities, the god most closely associated with water, thunder, and rainfall is Enlil. Enlil, one of the most powerful gods in the Sumerian and Akkadian mythology, was known as the god of air, wind, and storms. He was believed to control the weather and the atmosphere, and by extension, he had dominion over rain and thunder.

Another deity worth mentioning is Adad (also known as Hadad or Ishkur in Sumerian mythology), who was specifically the god of storms and thunder. Adad was revered for his ability to bring rain and thunder, which were crucial for agriculture in the Mesopotamian region.

While Enlil and Adad were not primarily water gods (like Enki/Ea, who was the god of water, knowledge, mischief, crafts, and creation), their association with storms and rainfall indirectly connects them to the element of water.

Bushmen (San People)

- Location: The San people are widely distributed across various countries in Southern Africa, including Botswana, Namibia, Angola, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Lesotho, and South Africa.

- Language: They speak a variety of languages, many of which include the distinctive click consonants. These languages are part of the Khoisan language group.

- Culture and Livelihood: Traditionally, the San are known for their hunter-gatherer lifestyle, living in small, mobile groups and relying heavily on their knowledge of the environment. They have a rich oral tradition and are renowned for their rock art.

- History: The San people are considered to be among the oldest inhabitants of Southern Africa, with a history that stretches back tens of thousands of years. They have faced significant challenges due to colonial expansion, loss of land, and modernization.

- Modern Challenges: Many San communities today face issues related to land rights, economic marginalization, and cultural survival. While some continue to practice traditional lifestyles, others have been integrated into farming or urban environments.

- Their history is deeply intertwined with the history of humans in Africa. Genetic studies suggest that the San carry some of the oldest human Y-chromosome haplogroups. These are often associated with the genetic diversity believed to be characteristic of the oldest human lineages. They are also thought to be direct descendants of the first Homo sapiens. Archaeological evidence of tools and rock art, attributed to ancestors of the San, dates back tens of thousands of years, with some estimates suggesting that they have been living in southern Africa for at least 20,000 years, and possibly much longer.

Believes of the San people

- Animism and Nature Worship: The San traditionally practice animism, believing that both living and non-living entities possess a spiritual essence. They hold a deep respect for the environment and see themselves as part of the natural world.

- Ancestral Spirits: Ancestors play a significant role in their spiritual beliefs. The San people often believe that the spirits of their ancestors reside in the natural world and can influence their lives. They perform rituals and ceremonies to honor these ancestors and seek their guidance and protection.

- Trance Healing and Dance: One of the most notable aspects of San spirituality is the trance dance, also known as the healing dance. During these dances, healers enter trance states to communicate with the spirit world. This state is believed to enable them to heal sickness, address social problems, and control the weather.

- Creation Myths and Folklore: The San have a rich set of myths and stories that explain the creation of the world and the origins of human beings. These stories are passed down orally and often feature animals and natural phenomena.

- Respect for Wildlife: The San are traditionally hunter-gatherers, and they have a profound respect for the animals they hunt. They often perform rituals before and after hunts to show respect to the animal spirits and to ensure balance in nature.

- Cosmology and Star Lore: The San also have a detailed understanding of the stars and celestial bodies. They incorporate this knowledge into their spiritual beliefs and everyday life, using it for navigation and timing of seasonal activities.

- Shamanism: Certain members of the community, often referred to as shamans, play a central role in the spiritual life of the San. They act as intermediaries between the physical world and the spiritual realm, using their knowledge and powers for healing and guidance.

Creation Myth of the San people

In this myth, Cagn is often portrayed as a trickster god, similar in some aspects to figures in other mythologies, such as Coyote in Native American lore or Loki in Norse mythology. He is sometimes depicted as taking on the form of a praying mantis, but he can transform into various animals.

- Creation of the World: In the beginning, Cagn created the world. Initially, everything was chaotic, and as he shaped the world, he had to fight and defeat many powerful and evil creatures.

- Creation of the First Human Beings: After making the world, Cagn fashioned the first human beings out of a tree. These first humans were very different from modern humans — they were immortal and lived in a world where there was no distinction between people and animals.

- The Gift of Fire and Hunting: Cagn is also credited with giving the San people fire and teaching them how to hunt. These gifts were crucial for their survival and became central aspects of their culture.

- Introduction of Death: According to some versions of the myth, Cagn’s own family plays a role in the introduction of death into the world. In one tale, Cagn’s daughter, a beautiful eland, is killed, and this event introduces death to the human experience. In another version, it is Cagn’s son who disobeys his instructions and brings death into the world.

- Shaping the Features of the World: Cagn is also often involved in shaping the features of the natural world, including creating mountains, rivers, and other natural features.

- The Moon and the Hare: Another notable story involves how the moon came to be. In this tale, the moon sends a message to humans through a hare, saying that like the moon waxes and wanes but always returns, so will humans die and come back to life. However, the hare misdelivers the message, saying that humans will die and not return, which angers the moon. As punishment, the moon hits the hare, splitting its lip, which is why hares have a split upper lip.

A race of Jinn before the creation of Adam

It is related in histories, that a race of Jinn, in ancient times, before the creation of Adam, inhabited the earth, and covered it, the land and the sea, and the plains and the mountains; and the favours of God were multiplied upon them, and they had government, and prophecy, and religion, and law; but they transgressed and off ended, and opposed their prophets, and made wickedness to abound in the earth; whereupon God, whose name be exalted, sent against them an army of Angels, who took possession of the earth, and drove away the Jinn to the regions of the islands, and made many of them prisoners …

Zakariya al-Qazwini, cosmographer Source

Names of little people in myth stories

- Middle East

- Djinn/Jinn

- Bhoots or Jinn

- Talu

- Arzshenk

- Gnomes (European)

- Daeva

- Divs

- Chaldean

- Peris

- Pazuzu

- The Armen

- Shedim

- Gul

- Africa

- Americas

- Jogah

- Gahongas

- Gandayah

Little people in the Middle East

Subterranean Dwarfs (Iranian Folklore)

The concept of subterranean dwarfs in Iranian folklore is a fascinating aspect of Persian mythical traditions. These dwarfs, often depicted as small, wise, and mysterious beings, are believed to inhabit the underground world. Their association with guarding treasures and possessing knowledge of the earth’s secrets ties them to ancient beliefs about the underworld and its riches.

- In some Persian tales, some dwarfs are believed to live underground.

- underground dwellers are often imagined as protectors of immense wealth, usually in the form of gold, jewels, and other precious items hidden deep within the earth.

- credited with deep knowledge of the earth, including the location and properties of minerals and gems

Djinn/Jinn (Widespread in Islamic Mythology)

Prominent in the folklore of the Middle East and Islamic cultures, including regions like Egypt, Iran, and Iraq. Djinn are supernatural beings that can come in various forms, and some traditions describe them as small or dwarf-like.

In various Middle Eastern cultures, Jinn are sometimes believed to inhabit mines or natural underground formations. These Jinn are thought to guard the treasures of the earth and can either help or hinder miners, depending on how they are treated.

Quranic and Islamic References

Djinn are mentioned in the Quran, which describes them as beings created from smokeless fire by Allah. Unlike humans, who were made from earth, Djinn exist in a world parallel to mankind. They have free will, can be good or evil, and are accountable to God on the Day of Judgment. One of the most famous Djinn in Islamic tradition is Iblis (Satan), who refused to bow to Adam and was consequently expelled from paradise.

Pre-Islamic Origins

The belief in Djinn predates Islam. In ancient Arabian religion, they were thought to be spirits of nature or deities of specific places. With the advent of Islam, these beliefs were integrated into a monotheistic framework, transforming Djinn into creatures subordinate to the one God but still retaining some of their earlier characteristics.

Abilities and Characteristics

Djinn are considered to be invisible to most humans, though they can make themselves visible if they choose. They possess immense strength, the ability to travel large distances quickly, and the power to shape-shift into various forms, including animals and humans. Some traditions also attribute to them the ability to possess and influence humans.

Types of Djinn

Islamic tradition mentions different types of Djinn.

- The Ifrit are considered to be powerful and rebellious

- The Marid are known for their strength and arrogance.

- The Ghoul is a type of Djinn believed to inhabit places like graveyards and deserts and is known for tricking travelers.

Cultural Significance

In various cultures, tales of Djinn are prevalent in folklore, where they often play the role of complex, sometimes malevolent, other times benevolent, entities. They are a common subject in Middle Eastern and Islamic literature, most famously in “One Thousand and One Nights” (Arabian Nights), where they appear in numerous stories.

Interaction with Humans

In folklore, Djinn are known to interact with humans, sometimes marrying them or bearing children. They can also be bound to a service, which is a common theme in magical stories involving Djinn.

Bhoots or Jinn (Afghanistan Folklore)

Similar to the broader concept of Djinn in Islamic mythology, in Afghanistan, there are tales of Bhoots or Jinn that can be small, mischievous spirits. They are often associated with specific places or natural elements.

Talu (Mesopotamian Mythology)

In ancient Mesopotamian belief, there were beings known as Talu, which are described in some texts as small, subterranean creatures. They were believed to inhabit the earth’s depths, possibly including areas where mining would occur.

Subterranean Creatures

The Talu are described as small, subterranean creatures. This aligns with a common theme in many ancient mythologies, where beings dwelling in the earth are often associated with specific aspects of the underworld or the earth’s mysteries, such as mining areas or natural resources.

Connection to Mining and Earth’s Riches

Given their supposed habitat in the earth’s depths and possible association with mining areas, the Talu might have been thought to have some control over or connection to the minerals and resources found underground. This could include guarding treasures or possessing knowledge about hidden natural riches.

Arzshenk (Armenian Mythology)

In Armenian legend, Arzshenk is a small, goblin-like creature that lives underground. It is said to be a guardian of treasures and minerals in the earth, making it directly relevant to mines.

Gnomes (Middle Eastern and European Influence)

While more commonly associated with European folklore, the concept of gnomes – small, earth-dwelling creatures skilled in mining and metalwork – has also found its way into Middle Eastern lore, especially in esoteric and mystical traditions.

Daeva (Zoroastrianism, Ancient Persia)

In Zoroastrianism, the Daevas are often depicted as demonic beings. Some legends describe them as subterranean creatures who could potentially be linked to the underworld or underground places like mines.

Divs (Persian and Zoroastrian Mythology, Iran)

These are malevolent beings, often depicted as monstrous and demonic, but some tales describe them as small and cunning creatures causing mischief or harm to humans.

Chaldean Mythical Beings (Ancient Mesopotamia)

In Chaldean mythology, there are references to various earth spirits and beings, some of which were believed to dwell underground. These entities might have been thought to inhabit or guard areas rich in natural resources, including mines.

Peris (Persian Mythology, Iran)

In ancient Persian mythology, Peris are often described as beautiful, winged, fairy-like beings. They are sometimes considered to be benevolent and miniature in size, inhabiting a world parallel to ours.

Pazuzu (Mesopotamian Mythology, Iraq)

Although not exactly a ‘little person’, Pazuzu is a demon of ancient Mesopotamian religion, often depicted as a combination of animal and human parts. He is included here due to his significant role in Mesopotamian folklore and his connection to the supernatural world.

The Armen (Armenian Mythology)

In Armenian folklore, there are stories of small, elf-like creatures known as the Armen. They are often described as living in forests or rural areas, sometimes helping and other times tricking humans.

Shedim (Jewish Mythology)

In Jewish folklore, which has influenced traditions in regions like Egypt and the broader Middle East, Shedim are spirits or demons. Though not always described as small, some interpretations or stories might depict them as diminutive beings.

Gul (Turkic and Persian Mythology)

In Turkic and Persian lore, Guls are a type of demon, often described as monstrous. However, in some tales, they are depicted as smaller, impish creatures that can be mischievous or malevolent.

Little people in Africa

Abatwa (Zulu and Xhosa Mythology)

In South African folklore, particularly within the Zulu and Xhosa cultures, the Abatwa are said to be tiny people riding ants. They are so small that they can hide beneath a blade of grass. These beings are reputed to be excellent hunters and are often associated with magic and hidden knowledge. Although not directly linked to mines, their diminutive size and their association with the earth align with the thematic elements you’re interested in.

Maabara (Sukuma Mythology)

In the mythology of the Sukuma people in Tanzania, Maabara are dwarfish creatures who are believed to live underground. They are often associated with mining as they are thought to possess the ability to indicate where miners can find valuable minerals. They are also believed to protect the mines and can bring good fortune to respectful miners while causing trouble for those who displease them.

The Tikoloshe (Zulu Mythology)

The Tikoloshe is another mythical creature from Zulu folklore. It is considered a mischievous and evil spirit that can become invisible by drinking water. It is said to be a dwarf-like creature, and while not specifically associated with mines, its underground dwelling and troublesome nature might be a connection.

Mmoatia (Ashanti Mythology, Ghana)

In Ashanti folklore, the Mmoatia are small, woodland creatures known for their mischievous behavior. They are often depicted as having a close association with the forest and natural world. While not directly linked to mines, their connection to the earth and natural elements is notable.

Agogwe (East African Folklore)

The Agogwe are little human-like creatures reported in the forests of East Africa. Described as small, hairy, and bipedal, they are said to live in the dense forests and could be related to elemental spirits of nature, similar to the concept of dwarves or elves in other mythologies.

Aziza (Fon and Yoruba Mythology, West Africa)

The Aziza are a beneficial fairy folk in the mythology of the Fon and Yoruba people. They are said to live in the forest and provide good fortune to hunters. They are also known for their wisdom and are sometimes depicted as guides or protectors of the natural world.

Biloko (Central African Folklore)

In the folklore of several Central African tribes, Biloko are dwarfish creatures believed to inhabit the deep forests. They are often depicted as spirits of ancestors or guardians of the forest, fiercely protective of the natural resources found there. While not specifically associated with mines, their protective nature over natural resources might be relevant.

Hawane (Swazi Mythology)

The Hawane are mythical little people in Swazi folklore. They are believed to be small in stature but powerful in magic, living in the mountains and forests. They are often associated with the protection of the environment and natural resources.

Kaukus (Berber Mythology, North Africa)

In Berber mythology, Kaukus are small, elf-like beings believed to inhabit the deserts and mountainous regions of North Africa. They are often described as being skilled in magic and having a deep connection to the land.

Adze (Ewe Mythology, Ghana and Togo)

In Ewe folklore, the Adze is a supernatural creature that can take the form of a firefly, but if captured, it turns into a humanoid vampire. This creature is often associated with the forests and the night. While not directly related to mines, the Adze’s connection to the supernatural and the natural world is quite strong.

Djinn or Jinn (North African and Swahili Coast)

In North African and Swahili coast cultures, Djinn are supernatural beings that can take various forms. Some Djinn are believed to be small or dwarfish. Their stories are widespread across the Islamic world and are well-known for their ability to interact with the physical world in both beneficial and malevolent ways.

Duendes (Cape Verdean Creole Folklore)

In the folklore of Cape Verde, Duendes are small, mischievous creatures. Although more known in Iberian and Latin American folklore, in Cape Verde, they represent a blend of African and Portuguese influences. They are often associated with the natural world and magical occurrences.

Sasabonsam and Asanbosam (Akan Mythology, Ghana)

In Akan folklore, Sasabonsam and Asanbosam are vampiric creatures often described as having features of both humans and bats, with elements of small stature in some descriptions. They are believed to inhabit the deep forests and are feared by locals.

Ninki Nanka (West African Folklore)

Found in the folklore of several West African cultures, Ninki Nanka is a mythical creature often described as a dragon-like being, but in some versions, it is depicted as small and elusive. Its habitat is said to be in the swamps and rivers of West Africa.

Tokoloshe (Southern African Folklore)

Similar to the Tikoloshe mentioned earlier, but in other Southern African cultures, the Tokoloshe may vary in description and lore. Often portrayed as malevolent, these small, dwarf-like creatures are believed to be summoned by malevolent people to cause trouble for others.

Hili (Swahili Folklore)

In Swahili folklore, Hili are small, elf-like beings known to live in forests and near rivers. They are often described as mischievous but can be helpful to those who respect the natural world and its rules.

Americas

Jogah

In Iroquois lore, the mythical “little people” known as the Jogah, or Drum Dancers. They usually remain unseen, but there exist methods to detect their presence. One such indication is the occurrence of drumming sounds in the absence of visible drummers. Additionally, they leave distinct marks such as rings of exposed earth and “bowls” in stones or mud, where offerings like tobacco and fingernails can be placed. The Jogah also offer an explanation for phenomena such as disembodied lights and misfortune.

Those who have encountered the Jogah, typically including children, elders, and spiritual healers, describe them as beings ranging from knee-high to approximately 4 feet (1.22 meters) (1.22 meters (4 feet)) in height. In terms of behavior, the Jogah exhibit a penchant for games and pranks, which can become hazardous if they are not treated with respect. It has been asserted that they can induce illness in homes and communities situated on sites that attract their attention.

The Jogah are categorized into several distinct groups, each with its unique characteristics.

The Gahongas

The Gahongas, often referred to as “stone throwers or rollers,” inhabit rocky terrains such as streams. Their favored pastime involves playing a form of “catch” with people, utilizing stones, some of which are as substantial as boulders.

The Gandayah

The Gandayah, on the other hand, assumes responsibility for the well-being of the local flora, instructing it when to grow and predicting the quality of its yield. They are known to aid respectful Iroquois farmers and harbor an affinity for strawberries. Depending on the nature of their message, they may take on the forms of American robins (for positive news) or owls (for negative news).

Finally, the Ohdows are the subterranean guardians tasked with safeguarding our world from creatures originating from the underworld, which could spread disease and chaos. These creatures emerge from the depths at night to engage in dance and hunt any underworld beings that may have escaped. To assist them in this mission, offerings in the form of fingernails are left, as the creatures from the underworld are capable of recognizing the scent of the Ohdow and seek to avoid them.

Each Haudenosaunee village had a Hage’ota or storyteller who was responsible for learning and memorizing the ganondas’hag or stories. Traditionally, no stories were told during the summer months in accordance with the law of the dzögä́:ö’ (transl. Little People). Source

Mines & Tunnels

The Ngwenya Mine is estimated to be around 43,000 years old, making it one of the oldest mines known to humans.