Table of Contents

- Akitu Festival in Mesopotamia

- Parallels in Canaanite and Surrounding Cultures

- Historical and Cultural Context

- Timing and Duration

- Key Rituals and Activities

- Symbolism and Purpose

- Variations and Evolution

- Temples

- Esagila

- Etemenanki

- House of Akitu (Bit Akitu)

- Temples in Other Cities

- Temple of Ashur

- Temple of Nabu (Ezida)

- Temple of Enlil (Ekur)

- General Practices in Temples

See also: Atlantis: The Last Days

Akitu Festival in Mesopotamia

The Akitu festival was celebrated twice a year in ancient Mesopotamia, most notably at the beginning of the Babylonian calendar’s first month, Nisannu (March-April), and again in the seventh month, Tashritu (September-October).

The festival typically lasted for 12 days.

Parallels in Canaanite and Surrounding Cultures

While direct evidence for New Year festivals for Chemosh, Milcom, and Baal is limited, we can infer that similar agricultural and renewal themes would have been present, possibly aligned with key agricultural cycles:

Spring Festivals (March-April)

- Purpose: To celebrate the renewal of life and the beginning of the agricultural year.

- Activities: Sacrifices, feasting, processions, and rituals to ensure a bountiful harvest.

- Analogous to: The Mesopotamian Akitu festival in Nisannu.

Autumn Festivals (September-October)

- Purpose: To mark the end of the agricultural year and prepare for the coming winter.

- Activities: Harvest celebrations, offerings of first fruits, and rituals to thank the deities for their protection and blessings.

- Analogous to: The Akitu festival in Tashritu.

The Akitu Festival, also known as the Akitu or Akitum, was an important religious celebration in ancient Mesopotamia, particularly in Babylon and Assyria. It was primarily associated with the Babylonian god Marduk and the renewal of kingship and the cosmos. Here are the key aspects of the Akitu Festival:

Historical and Cultural Context

- Origins: The Akitu Festival has its origins in the Sumerian civilization and was later adopted and elaborated by the Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians.

- Significance: The festival marked the New Year and was held to ensure the renewal of the earth, the king, and society. It symbolized the victory of the god Marduk over the forces of chaos.

Timing and Duration

- Date: The primary Akitu Festival was celebrated at the beginning of the Babylonian calendar’s first month, Nisannu (March-April). There was also a secondary festival in the seventh month, Tashritu (September-October).

- Duration: The festival typically lasted for 12 days, though the exact length could vary.

Key Rituals and Activities

Preparations

- Purification: The festival began with purification rituals, including cleaning the temple and the city.

- Statue of Marduk: The statue of Marduk was central to the ceremonies and was prepared for the upcoming events.

Processions

- Gods’ Procession: Statues of gods from various temples in Babylon and nearby cities were brought to the Esagila, Marduk’s temple.

- Community Participation: Citizens participated in processions, singing hymns and offering sacrifices.

Rituals in the Esagila

- Enuma Elish Recitation: The Babylonian creation epic, “Enuma Elish,” was recited, recounting Marduk’s victory over Tiamat and the creation of the world.

- Humiliation and Restoration of the King: The king was ritually humiliated by the high priest, symbolically stripped of his regalia, and made to swear his loyalty to Marduk. He was then reinstated as king, reaffirming his divine mandate.

Battle Reenactment

- Combat Drama: A ritual reenactment of Marduk’s battle against Tiamat, representing the cosmic struggle between order and chaos, was performed.

Sacrifices and Feasting

- Offerings: Extensive sacrifices of animals and other offerings were made to Marduk and other gods.

- Communal Feasts: Large communal meals were held, fostering social unity and collective participation in the festival.

Journey to the House of Akitu

- Temple Outside the City: On the final days, Marduk’s statue was taken to the “House of Akitu,” a special temple located outside the city, symbolizing his triumphal return and the renewal of his powers.

- Return Procession: The statue was then brought back to the Esagila, completing the cycle of renewal.

Symbolism and Purpose

- Cosmic Renewal: The Akitu Festival was seen as a time to renew the cosmos, ensuring the continued order and stability of the world.

- King’s Legitimacy: The rituals emphasized the king’s divine right to rule, reinforcing his authority and connection to the gods.

- Community and Identity: The festival fostered a sense of community and collective identity among the participants, uniting them in shared religious and cultural practices.

Variations and Evolution

- Assyrian Adaptations: In Assyria, the Akitu Festival included elements specific to the Assyrian pantheon and political context, though many core elements remained similar to the Babylonian tradition.

- Continuity and Change: While the Akitu Festival persisted through various political changes, its details and emphasis evolved over time, reflecting the shifting religious and political landscape of Mesopotamia.

Temples

Temples played crucial roles during the Akitu Festival in ancient Mesopotamia. The most important of these were associated with the chief deity of the city-state, particularly Marduk in Babylon. Here are the key temples involved in the Akitu Festival:

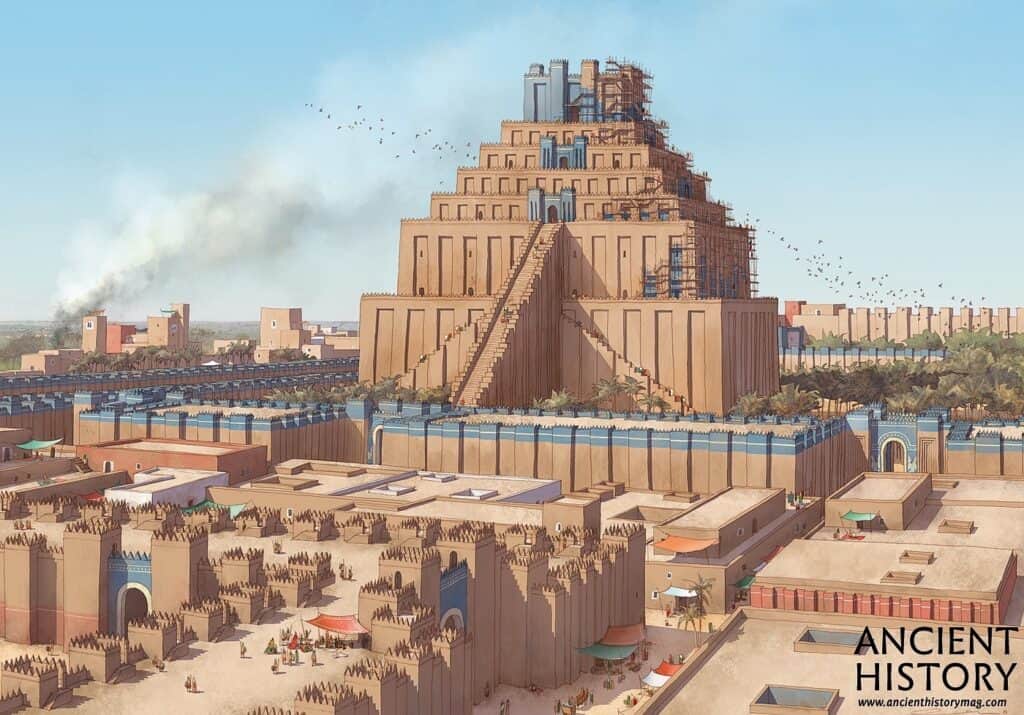

Esagila

- Location: Babylon

- Deity: Marduk

- Significance: Esagila was the main temple of Marduk in Babylon and the central site for the Akitu Festival. The temple complex included the ziggurat Etemenanki, which was considered the earthly residence of Marduk. Many of the festival’s critical rituals took place in Esagila, including the recitation of the “Enuma Elish,” the ritual humiliation and restoration of the king, and other ceremonial activities.

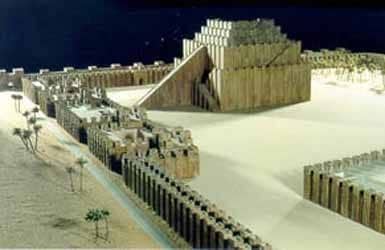

Etemenanki

- Location: Babylon

- Deity: Marduk

- Significance: Etemenanki was the great ziggurat of Babylon, often identified with the biblical Tower of Babel. It was an essential part of the Esagila complex and symbolized the connection between heaven and earth. During the Akitu Festival, processions and rituals highlighted the ziggurat’s significance as a central religious and cosmological axis.

House of Akitu (Bit Akitu)

- Location: Outside Babylon

- Deity: Marduk

- Significance: The Bit Akitu, or House of Akitu, was a special temple located outside the city walls of Babylon. It was used during the final days of the festival. Marduk’s statue was taken in a procession to this temple, symbolizing his journey to the underworld and return, representing renewal and rebirth. This journey mirrored the cosmic battle and renewal themes central to the festival.

Temples in Other Cities

While Babylon’s Akitu Festival is the most well-documented, other Mesopotamian cities also celebrated similar festivals for their principal deities:

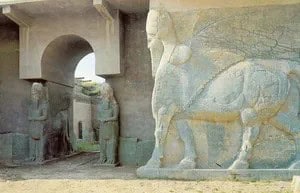

Temple of Ashur

- Location: Assur (Ashur)

- Deity: Ashur

- Significance: In the Assyrian city of Assur, the temple of Ashur was central to their New Year celebrations, which included elements similar to the Babylonian Akitu Festival. Ashur, the chief deity of the Assyrians, was honored with rituals affirming his supremacy and the king’s divine mandate.

Temple of Nabu (Ezida)

- Location: Borsippa

- Deity: Nabu

- Significance: Nabu, the god of wisdom and writing, was another important deity during the Akitu Festival. His temple, Ezida, in Borsippa (near Babylon), was involved in the festivities. Nabu’s role in the festival underscored the themes of wisdom, order, and renewal.

Temple of Enlil (Ekur)

- Location: Nippur

- Deity: Enlil

- Significance: Nippur, the religious center of Sumer, celebrated a similar festival for Enlil, the chief deity of the Sumerian pantheon. The Ekur temple in Nippur was central to these celebrations, focusing on Enlil’s role in maintaining cosmic order and blessing the land.

General Practices in Temples

During the Akitu Festival, these temples hosted a variety of rituals:

Purification Ceremonies: Temples were purified to prepare for the divine presence.

Recitations and Rituals: Sacred texts, like the “Enuma Elish,” were recited to recount the gods’ victories and the creation of the world.

Processions: Statues of the gods were taken from their temples in elaborate processions, often moving between temples to symbolize journeys through the cosmos.

Sacrifices and Offerings: Animals, food, and other offerings were presented to the gods to seek their favor and blessings for the coming year.