Table of Contents

- Explanation of the Row “Pre-dynastic Rulers”:

- Who are the 25 kings that ruled during the Pre-dynastic period?

- Notable Rulers and Chiefdoms:

- Potential Rulers from Archaeological Sites:

- Regional Chiefs and Proto-Kings:

- Sources and Evidence:

- Spirits of the Dead

- Followers of Horus:

- Key Points:

- Turin Royal Canon

- Followers of Horus (Pre-Dynastic Rulers)

- Fragmentary and Hypothetical Rulers

- Other Possible Names

- Challenges in Reconstructing the List

- Historical Context:

- Badarian Period

- Naqada Period

- Evidence of Rulers During the Naqada Period:

- Archaeological Sites

- Key radiocarbon-dated tombs and artifacts

- Notes:

The term “Pre-dynastic Rulers” refers to the period in ancient Egyptian history before the establishment of the first historical dynasty. It is placed after the ruler Horus and before the 1st dynasty.

This era is characterized by the formation and development of the early Egyptian state, leading up to the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the first pharaoh of the 1st Dynasty.

Explanation of the Row “Pre-dynastic Rulers”:

- Reign Start (BCE):

- This marks the approximate beginning of the pre-dynastic period, which is based on archaeological evidence of early settlements and cultural development in the Nile Valley.

- Reign End (BCE):

- This marks the end of the pre-dynastic period and the beginning of the dynastic period with the establishment of the 1st Dynasty by Pharaoh Narmer, who is often credited with unifying Egypt.

- Total Span (Years): 1900 years

- This represents the total duration of the pre-dynastic period, covering about 1900 years of early Egyptian history.

- Number of Kings: 25

- This is an estimated number of rulers who might have reigned during the pre-dynastic period. It is based on archaeological and historical evidence suggesting multiple local chieftains or proto-pharaohs who ruled different regions of Egypt before its unification.

Who are the 25 kings that ruled during the Pre-dynastic period?

The identification of specific rulers during the pre-dynastic period of Egypt is challenging due to the limited and often ambiguous archaeological evidence. The term “pre-dynastic period” typically refers to the era before the unification of Egypt under the first pharaoh of the 1st Dynasty, which is traditionally dated to around 3100 BCE. This period is characterized by regional chiefdoms and early kingships, particularly during the Naqada III phase (also known as the Protodynastic period).

While exact names and detailed accounts of these rulers are scarce, some notable figures and titles have been identified through various archaeological discoveries. Here are some of the prominent rulers or chiefdoms from this period:

Notable Rulers and Chiefdoms:

- Scorpion King (Scorpion I)

- Often associated with Tomb U-j at Abydos, dating to the Naqada III period. This ruler’s name appears in early inscriptions.

- Scorpion II

- Another ruler named Scorpion, possibly distinct from Scorpion I, is depicted on the Scorpion Macehead found at Hierakonpolis.

- Narmer

- Considered by many as the unifier of Egypt and the first pharaoh of the 1st Dynasty, Narmer is often associated with the Narmer Palette, which depicts the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt.

- Ka (Sekhen)

- A pre-dynastic ruler whose name is found inscribed in tombs at Abydos. He is sometimes considered one of the last rulers before the 1st Dynasty.

- Iry-Hor

- Another early ruler whose name appears in inscriptions at Abydos. His exact role and position in the timeline are still subjects of research and debate.

Potential Rulers from Archaeological Sites:

- Crocodile (possibly symbolic or actual ruler)

- Mentioned in inscriptions and associated with the Crocodile Macehead, suggesting early kingship symbolism.

Regional Chiefs and Proto-Kings:

While specific names are limited, various regions during the Naqada III period had local chieftains or proto-kings. These regions include:

- Hierakonpolis (Nekhen)

- An important political and religious center in Upper Egypt, home to early elite burials and symbols of kingship.

- Naqada

- Another major center, giving its name to the cultural phases of pre-dynastic Egypt.

- Abydos (Thinis)

- A significant burial site for early rulers, including those mentioned above.

10-25. Other Local Rulers and Chieftains: – Various other regional rulers and chieftains existed, ruling smaller territories or city-states. These figures are less well-documented, but they played crucial roles in the political landscape of pre-dynastic Egypt.

The estimation of 25 kings ruling during the pre-dynastic period is not based on a single definitive source but rather on a combination of archaeological evidence, historical inference, and scholarly consensus. Here’s how this number is derived:

Sources and Evidence:

- Manetho’s King List:

- Manetho was an Egyptian priest and historian who compiled a list of kings in the 3rd century BCE. His work, though fragmented, suggests a lineage of rulers predating the 1st Dynasty, often referred to as “Spirits of the Dead” or “Followers of Horus.”

- Archaeological Findings:

- Excavations at key sites such as Abydos, Hierakonpolis, and Naqada have revealed tombs and inscriptions of pre-dynastic rulers. These findings include:

- Tomb U-j at Abydos, attributed to a ruler named Scorpion.

- Other significant burials and early inscriptions from the Naqada III period, indicating the existence of multiple rulers.

- Excavations at key sites such as Abydos, Hierakonpolis, and Naqada have revealed tombs and inscriptions of pre-dynastic rulers. These findings include:

- Inscriptions and Artifacts:

- Early hieroglyphic inscriptions and symbols of kingship (e.g., serekhs) found on pottery, tags, and other artifacts provide evidence of various rulers.

- The Narmer Palette, which depicts the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt, hints at a lineage of rulers leading up to Narmer.

- Regional Chiefs and Proto-Kings:

- The Naqada III period, also known as the Protodynastic period, saw the emergence of regional chiefdoms and proto-kings. Each of these local rulers contributed to the complex political landscape.

- Sites like Hierakonpolis (Nekhen), Naqada, and Abydos were prominent centers of power, each likely ruled by different chiefs or kings.

Spirits of the Dead

The “Spirits of the Dead” and the “Followers of Horus” refer to ancestral rulers mentioned in ancient Egyptian traditions and texts. These groups are thought to represent the kings and chieftains who ruled Egypt before the establishment of the historical dynasties, particularly those who reigned during the pre-dynastic and early dynastic periods.

The “Spirits of the Dead” (also called “Shem-Su-Hor” or “Followers of Horus”) are mentioned in ancient Egyptian texts and king lists, such as those compiled by Manetho and in the Turin Royal Canon.

In some contexts, they are thought to be mythical ancestors who served as intermediaries between the gods and humans, establishing the divine right of kings to rule.

Followers of Horus:

The “Followers of Horus” are closely associated with the early dynastic kingship and are often depicted in the context of the unification of Egypt.

Horus, the falcon-headed god, was a symbol of kingship and protection, and his followers were seen as his earthly representatives.

These followers or “companions” of Horus are believed to have been the early rulers who helped consolidate power in Upper and Lower Egypt, leading up to the unification under a single ruler.

Key Points:

Manetho’s King List: Manetho, an Egyptian priest and historian from the Ptolemaic period, mentions a series of divine and semi-divine rulers preceding the historical dynasties.

Turin Royal Canon: This papyrus, also known as the Turin King List, includes a section that lists the pre-dynastic rulers as “Followers of Horus.”

These figures symbolize the divine legitimacy of the pharaohs, reinforcing the idea that the rulers of Egypt were chosen by the gods to maintain order and harmony (Ma’at).

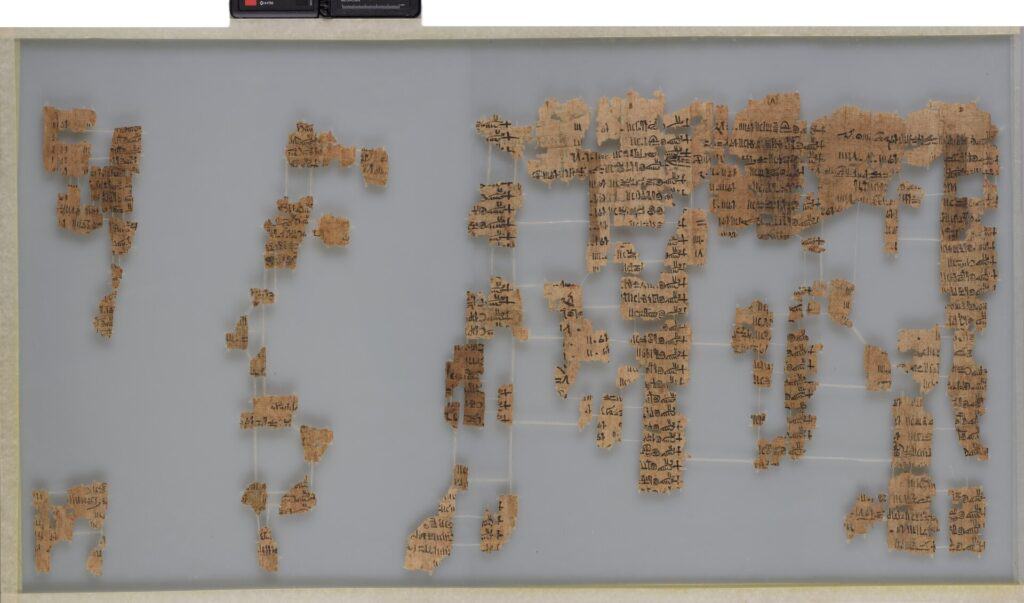

Turin Royal Canon

The Turin Royal Canon, also known as the Turin King List, is a papyrus document that provides a list of kings and is one of the most significant sources of information on the chronology of ancient Egypt.

However, the papyrus is heavily damaged and fragmentary, which makes it difficult to fully reconstruct the list of pre-dynastic rulers. The section that lists the “Followers of Horus” is particularly fragmentary, and the names of these early rulers are often missing or incomplete.

Despite the challenges, scholars have attempted to piece together some of the names from the Turin Royal Canon and other sources.

The following list includes some of the rulers traditionally associated with the “Followers of Horus” based on the Turin King List and other archaeological and historical evidence.

Note that the names and order are tentative and subject to scholarly interpretation:

Followers of Horus (Pre-Dynastic Rulers)

- Scorpion I

- Often associated with the early Naqada III period. Evidence of his reign comes from the tomb at Abydos (Tomb U-j).

- Iry-Hor

- One of the earliest known rulers, with his name found inscribed on jars and seal impressions at Abydos.

- Ka (Sekhen)

- Known from inscriptions in tombs at Abydos. His name is represented by the hieroglyph for “soul” (ka) within a serekh.

- Scorpion II

- Another ruler named Scorpion, depicted on the Scorpion Macehead found at Hierakonpolis. Sometimes considered distinct from Scorpion I.

- Narmer

- Credited with the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt. Known from the Narmer Palette, which depicts his military victories and the unification process.

Fragmentary and Hypothetical Rulers

- Hedju-Hor

- A ruler from the late pre-dynastic period, known from inscriptions and artifacts.

- Crocodile (Symbolic or Actual Ruler)

- Sometimes referred to in inscriptions and artifacts, possibly representing a symbolic or lesser-known local ruler.

Other Possible Names

The following names are more speculative and based on fragmentary evidence, often mentioned in various king lists and archaeological contexts:

- Tiu

- Thesh

- Hsekiu

- Wazner

- Mekh

- Neheb

- Uadjnar

- Nubnefer

- Seka

- Aha (or Hor-Aha)

Challenges in Reconstructing the List

- Fragmentary Nature: The Turin Royal Canon is significantly damaged, making it difficult to read many of the names accurately.

- Archaeological Evidence: Many of the names are inferred from archaeological evidence such as pottery inscriptions, seal impressions, and tomb remains.

- Scholarly Interpretation: Different scholars may interpret the evidence differently, leading to variations in the reconstructed lists.

Historical Context:

The pre-dynastic period is divided into several phases based on cultural and technological developments:

- Badarian Period

- Characterized by the earliest evidence of agriculture, animal husbandry, and pottery in Upper Egypt.

- Naqada I (Amratian) Period

- Known for advances in pottery, the development of social hierarchies, and increasing complexity in burial practices.

- Naqada II (Gerzean) Period

- Marked by significant cultural and technological developments, including more elaborate tombs, the use of copper tools, and increased trade with neighboring regions.

- Naqada III (Protodynastic)

- The final phase before the establishment of the 1st Dynasty, characterized by increased political centralization and the emergence of early hieroglyphic writing.

Naqada is not an individual but rather a significant archaeological site in Upper Egypt that has given its name to a key cultural phase in pre-dynastic Egyptian history. The term “Naqada” refers to both the site and the chronological phases of the pre-dynastic period, which are crucial for understanding the development of early Egyptian civilization.

Badarian Period

The Badarian culture is named after the site of El-Badari, located on the east bank of the Nile River in Upper Egypt. This area encompasses several key archaeological sites, including El-Badari itself, as well as Mostagedda and Matmar.

The first discoveries of Badarian artifacts were made in the early 20th century by British archaeologists Guy Brunton and Gertrude Caton-Thompson. Their excavations at El-Badari revealed numerous graves and a wide array of artifacts, providing a comprehensive picture of Badarian life and culture.

Naqada Period

- Naqada as an Archaeological Site:

- Location: Naqada is located on the west bank of the Nile River, approximately 26 kilometers (16.16 miles) north of Luxor.

- Significance: It is one of the most important pre-dynastic sites in Egypt and has provided extensive evidence of early Egyptian culture and society.

- Naqada Culture:

- The Naqada culture is divided into three phases: Naqada I (Amratian), Naqada II (Gerzean), and Naqada III (Protodynastic).

- These phases represent the progression and development of pre-dynastic Egyptian society, leading up to the unification of Egypt and the establishment of the 1st Dynasty.

- Phases of Naqada Culture:

- Naqada I (Amratian) Period (c. 4000–3500 BCE):

- Characterized by the production of black-topped red pottery, the use of stone tools, and early forms of social stratification.

- Evidence of trade with neighboring regions, as indicated by the presence of imported materials.

- Naqada II (Gerzean) Period (c. 3500–3200 BCE):

- Marked by increased sophistication in pottery, with more intricate designs and motifs.

- Development of larger settlements and more complex social structures.

- Use of copper tools and ornaments, indicating technological advancement.

- Growth of long-distance trade, with artifacts from this period found in regions as far as Mesopotamia.

- Naqada III (Protodynastic) Period (c. 3200–3100 BCE):

- The final phase before the establishment of the 1st Dynasty.

- Characterized by significant political centralization and the emergence of early forms of writing.

- Development of elaborate tombs and burial practices, indicating a more complex social hierarchy.

- This phase leads directly into the early dynastic period, marked by the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt.

- Naqada I (Amratian) Period (c. 4000–3500 BCE):

Evidence of Rulers During the Naqada Period:

Tombs and Burial Sites:

- Elite Tombs: The Naqada III period features large, elaborate tombs that indicate the presence of powerful individuals who were likely rulers or chiefs. These tombs often contain grave goods, such as pottery, jewelry, and weapons, which signify high status.

- Cemeteries: Sites like Abydos and Hierakonpolis have yielded significant burial sites with evidence of social stratification, suggesting the presence of a ruling elite.

Inscriptions and Symbols:

- Serekhs: The use of serekhs (an early form of royal crest) appears during this period. Serekhs typically contain a ruler’s name and are precursors to the royal cartouche. Examples have been found at sites like Abydos, indicating the names of early rulers.

- Hieroglyphs: Early hieroglyphic inscriptions from the Naqada III period, found on pottery and other artifacts, sometimes include the names of rulers.

Artifacts:

- Scorpion Macehead: One of the most famous artifacts from this period is the Scorpion Macehead, found at Hierakonpolis. It depicts a figure known as King Scorpion, who is shown performing a ceremonial activity, possibly related to irrigation or agriculture. This artifact suggests the existence of a ruler named Scorpion who had significant influence.

- Narmer Palette: The Narmer Palette, also from the late Naqada III period, is a significant artifact that depicts King Narmer, who is often credited with the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt. The palette shows Narmer wearing the crowns of both regions, symbolizing his rule over a unified Egypt.

Archaeological Sites

Abydos: This site contains some of the earliest evidence of royal burials, including those of rulers from the Naqada III period. Tomb U-j at Abydos, believed to belong to a ruler named “Scorpion,” contains inscribed tags and vessels, indicating the presence of early forms of writing and administrative control.

Hierakonpolis: Excavations at this site have revealed large ceremonial structures and elite tombs, providing evidence of powerful local rulers during the Naqada period.

Key radiocarbon-dated tombs and artifacts

Here’s a table listing some of the key radiocarbon-dated tombs and artifacts from the Naqada period, including their approximate dates, locations, and significant details:

| Site | Tomb/Artifact | Approximate Date (BCE) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abydos | Tomb U-j | c. 3200 BCE | Believed to belong to a ruler named Scorpion. Contains inscribed tags and vessels, providing early evidence of writing. |

| Hierakonpolis | HK6 Elite Cemetery | c. 3500–3200 BCE | Contains large tombs with rich grave goods, indicating high-status individuals. |

| Naqada | Tomb 100 | c. 3500 BCE | Known for its wall paintings, providing insights into early Egyptian art and culture. |

| Naqada | Naqada I and II Artifacts | c. 4000–3200 BCE | Various organic materials, including textiles and pottery, dated to these periods. |

| Abydos | Cemetery B | c. 3400–3100 BCE | Contains multiple burials from the Naqada III period, with radiocarbon-dated organic remains. |

| Hierakonpolis | Painted Tomb | c. 3500 BCE | Features some of the earliest known wall paintings in Egypt. |

| Naqada | Black-topped Pottery | c. 4000–3500 BCE | Typical of the Naqada I period, used for radiocarbon dating. |

| Hierakonpolis | HK29A | c. 3600 BCE | Early Naqada II site with significant burials and grave goods. |

| Maadi | Maadi Artifacts | c. 3900–3500 BCE | Organic remains and pottery from the Naqada I period, indicating early settlement and trade. |

| Adaïma | Tombs and Artifacts | c. 3500–3200 BCE | Numerous burials with organic materials, providing a wide range of radiocarbon dates. |

Notes:

- Tomb U-j at Abydos: This tomb is one of the most significant finds from the Naqada III period. The inscribed tags found here provide some of the earliest evidence of writing in Egypt.

- HK6 Elite Cemetery at Hierakonpolis: This site has yielded numerous elite burials, suggesting the presence of a powerful ruling class during the Naqada period.

- Tomb 100 at Naqada: Known for its wall paintings depicting scenes of boats, animals, and humans, offering insights into the cultural practices of the time.

- Painted Tomb at Hierakonpolis: Another significant find, this tomb contains early wall paintings that are important for understanding the development of Egyptian art.

- Maadi Artifacts: The site of Maadi provides important evidence of early trade and settlement patterns, with artifacts dating back to the Naqada I period.