Table of Contents

Göbekli Tepe, located in Turkey, is an ancient archaeological site dating back to around 9500 to 8000 BCE, based on carbon dating of the soil that covered the site.

It’s famous for its large circular structures with massive stone pillars, making them the world’s oldest known megaliths. These pillars are adorned with carvings of humans and wild animals, offering valuable insights into prehistoric beliefs and culture.

Initially thought to be a religious site used by nomadic hunter-gatherer groups, recent discoveries suggest it might have been a settlement. Experts are currently debating whether agriculture led people to settle down or if settled living enabled the growth of agriculture. Göbekli Tepe, standing on a rocky mountaintop without clear signs of farming, has been pivotal in this discussion.

The purpose of the site’s megalithic enclosures remains a mystery. Originally considered the world’s first temples, recent studies have shown that they were filled due to natural events, challenging earlier beliefs about intentional backfilling.

Discovered in 1963, Göbekli Tepe gained significant recognition in 1994 when excavations began. After the original excavator Klaus Schmidt’s death in 2014, the work continued as a joint effort involving Istanbul University, Şanlıurfa Museum, and the German Archaeological Institute, under the direction of Turkish prehistorian Necmi Karul. In 2018, it was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site for its exceptional architectural significance. Despite its importance, less than 5% of the site had been excavated as of 2021.

Göbekli Tepe and the Calendar Discovery

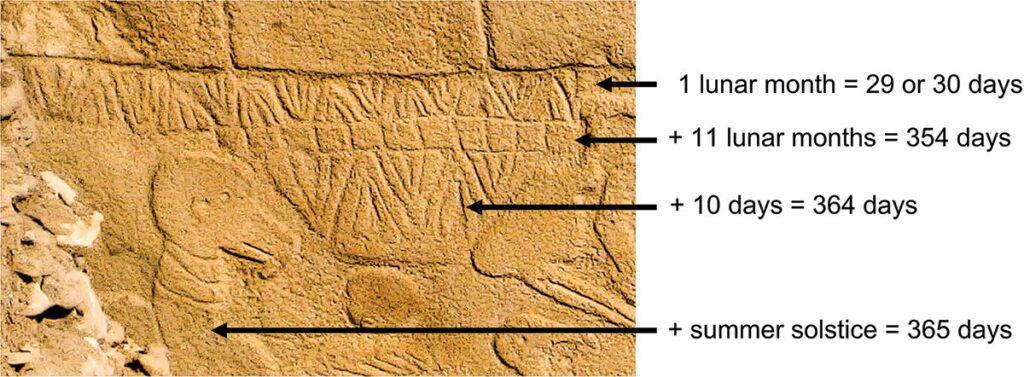

Recently, new interpretations have emerged about the site, particularly the research conducted by Martin Sweatman from the University of Edinburgh, which suggests that some of the carvings at Göbekli Tepe may represent one of the oldest known calendars in history.

Göbekli Tepe: Located near the Syrian border in Turkey, it consists of a series of stone circles and pillars, which are believed to have been used for ceremonial or religious purposes. The site predates known civilization and agriculture, making its complexity particularly intriguing to archaeologists.

Martin Sweatman’s Interpretation

Sweatman theorizes that the calendar was created to commemorate significant comet impacts that occurred around 10,850 BCE. These events may have triggered environmental changes, including a mini-ice age lasting approximately 1,200 years, affecting both the climate and the extinction of large animal species.

V-markings on Pillars: Sweatman has focused on specific markings found on the T-shaped pillars at Göbekli Tepe, interpreting them as elements of a calendar system. His research suggests that one of the pillars contains 365 “V” shaped markings, which he believes represent days in a solar year.

Symbolism: Each “V” marking is thought to symbolize a day, and the collection of these markings potentially represents a complete solar calendar, predating other known calendar systems by several millennia.

Significance of the Calendar

The precision with which dates were recorded suggests a sophisticated understanding of time and astronomy far earlier than previously believed. This capability may have influenced the development of agriculture and subsequent civilization advancements in the region, leading to the rise of early Mesopotamian cultures around 4,000 BCE.

Astronomical Understanding

Precursor to Written Language: Sweatman suggests that these early attempts to document astronomical events could represent the initial steps towards the development of writing systems, which emerged millennia later.

Comparison with Later Calendars: While the site predates other known calendar systems, the concept of combining solar and lunar cycles (lunisolar calendars) was used by various ancient cultures, indicating a long-standing human interest in tracking celestial phenomena.